I always went into writing with the belief that I am an outliner. I’m the kind of person who lives their life according to a cascading collection of one-, three-, five-, and ten-year plans, where each group of short-term goals feeds into a carefully considered set of long-term goals.

But in actual fact, I’m not. I’ll sit there, plan an outline, then throw it out when it’s time to put my fingers to the keyboard.

(You’d think I’d’ve realized this earlier; if I compare every ten-year plan I ever made to how my life unfolded, very little of those plans survived their encounters with reality.)

In my penultimate year of high school, I’d taken an elective in drama. I don’t remember much of the curriculum, other than what my teacher taught us about the rules of good improvisation: when your improvisation partner makes an ‘offer’, accepting and building upon that offer generally results in a better storytelling outcome.

That mindset was invaluable to me as I was drafting this book. Most of Petition was discovery-written, with many of the characters and plot lines springing into being during the writing process, prompted by my use of the “try/fail” cycle.

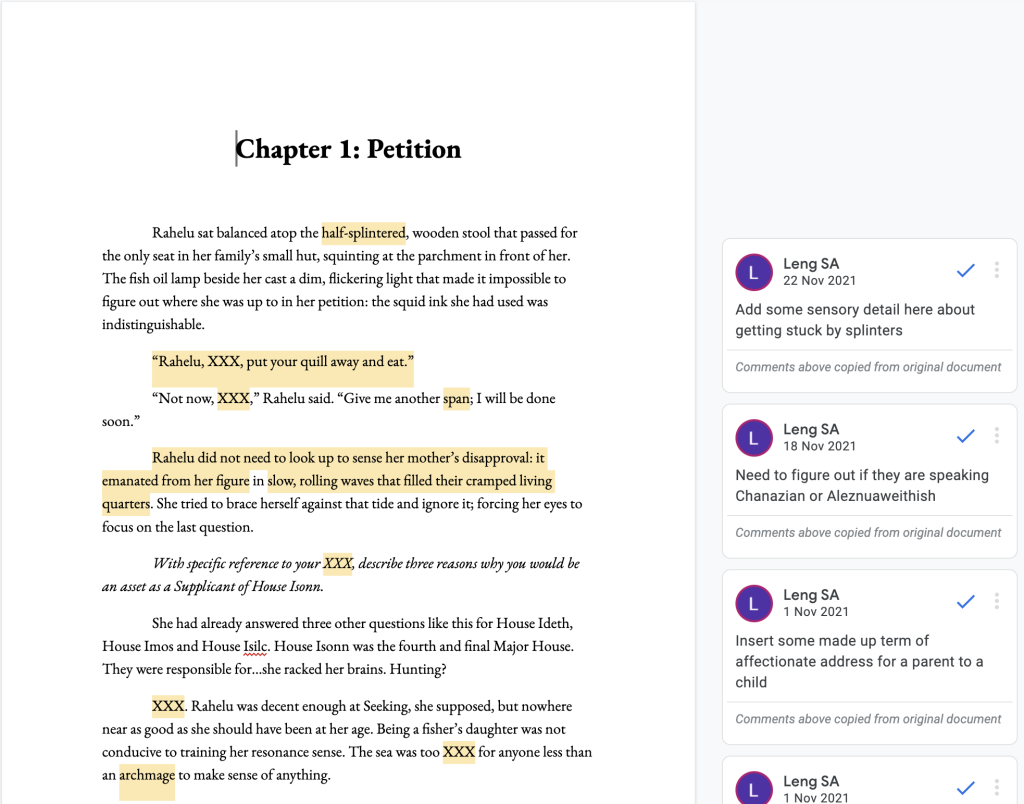

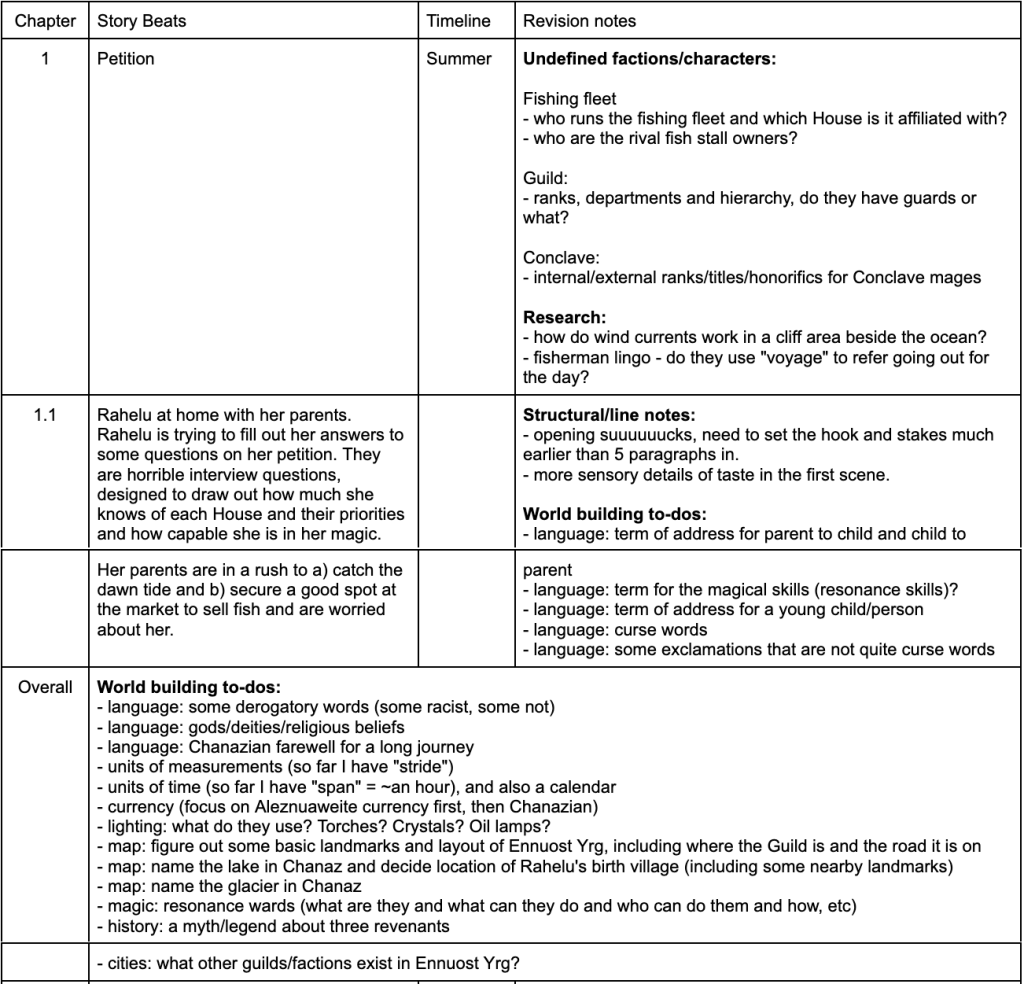

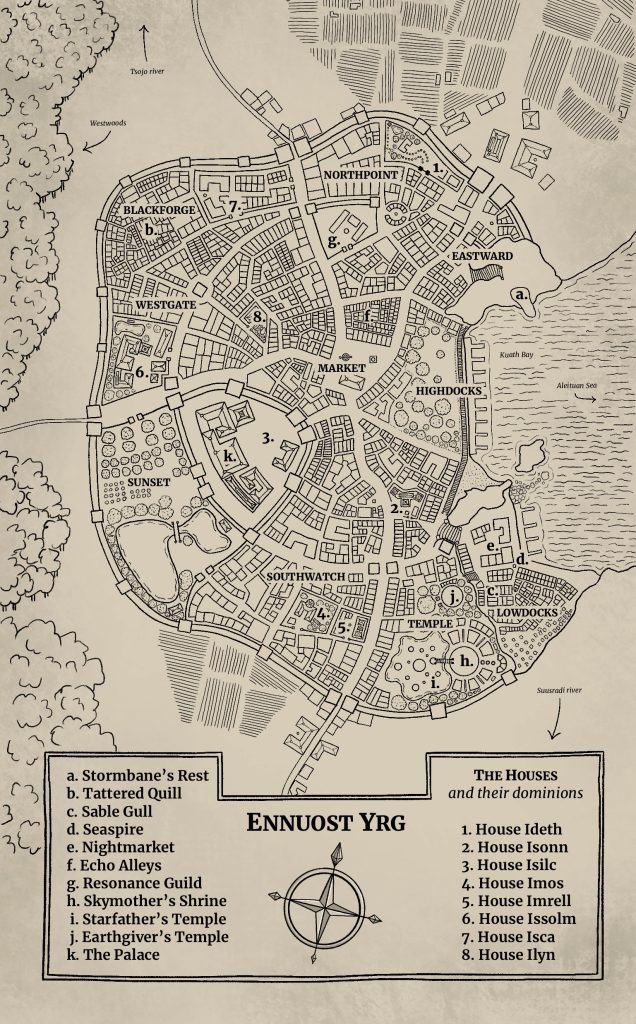

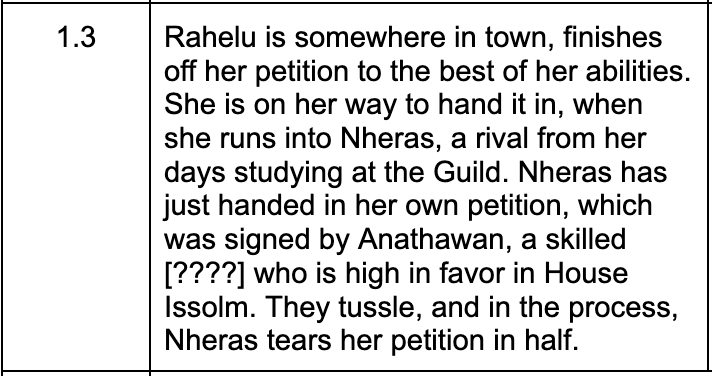

Here are my original notes for this chapter:

Where’s the discussion of scene 1.2, you ask? We’ll talk about that when we get to the annotations for Chapter 13! But this is what the opening of the market scene looked like in the very first draft:

There was no competitive parental sniping between Rahelu’s mother and Hzin. Bzel didn’t exist. I hadn’t figured out any of the worldbuilding logistics around commercial selling of fresh seafood when refrigeration technology (or magic) isn’t commonly available—I hadn’t even named my fantasy fish. All of those things were added in during later revisions.

Even so, the opening chapters were some of the fastest chapters to write. My writing progress tracker says I was writing new prose at a rate of 926–1,154 words per hour. If only I could write that fast all the time!

The first draft of the House-born sequence with Nheras came in at 1,995 words, which is on the short side for one of my action sequences. Here’s a copy of that scene, complete with all my XXX placeholders and inline comments bemoaning my terrible writing.

Much of that draft remains in the published version. But one of artifacts of discovery writing is that I did not know what kind of story I was writing. I did not yet know the details of the main conflicts or who the main characters, other than Rahelu, were going to be—let alone what their motivations were.

As a result, the first half of this book needed heavy structural revision. Here’s the tracked changes comparison between the original draft and the published version. Surprisingly, the revisions turned out to be less about changing story beats and more about fleshing out characters and adding in extra details to foreshadow later events and/or to reinforce themes.

Bzel

The little moment with Bzel and Rahelu’s almost-Evocation was written after I wrote the original prologue, which I subsequently cut and replaced with a new prologue. That ruined the reversal of perspectives you get in the ending, so I kept this moment here to try and maintain some of that symmetry.

Lhorne and Cseryl cameo

This was my attempt to make the ending of the book less weird, structurally speaking. (I’ll discuss the structural weirdness in more detail when we get to the annotations for Chapters 24 and onwards.) I’m not entirely sure it works, but it does lay some groundwork for later chapters with not a whole lot of word count so I left it in.

Deepening Nheras’s character

Like the vast majority of the cast, Nheras wasn’t a planned character—she popped up when I needed to give Rahelu an obvious antagonist early on. But once she became part of the narrative, I didn’t want to make her a disposable antagonist.

In the first draft, Nheras reads like a typical bully/‘Mean Girls’ trope character. That’s deliberate—we’re in Rahelu’s POV after all—but it’s also a problem. There are moments where she borders on being an outright caricature. (Is there anything that screams ‘cartoon villain’ more that a character siccing their cronies onto the protagonist with some sort of variation on “get ’em, boys”?)

I hate reading one-note characters. They make it difficult for me to suspend my sense of disbelief in the first place and they rob scenes of emotional impact. Why should I care if the funny sidekick dies or if the antagonist is overcome if they’ve been nothing more than cardboard cut-outs?

(You can’t necessarily do this with every character. I didn’t have the page count to give Bhemol and Kiran more depth: Rahelu views them as Nheras’s thugs and that’s all you need to know about them. Narratively speaking, they’re there to underscore the main conflict in the scene, which is the Nheras/Rahelu rivalry. I could have added more moments to show that there’s more to Bhemol and Kiran than being bullies, but that’s not the story I was trying to tell.)

Powerful emotional moments have to be earned. For me, the most memorable scenes—the ones that evoke strong, raw emotional responses when I’m reading—are always rooted in conflicts between multi-dimensional characters.

Easy to point out where an author has gone wrong, but hard to do right. I tried to do a couple of things with the expanded Nheras moments in this chapter:

- Create the sense of five years of history between Nheras and Rahelu.

- Let the reader come to the conclusion that there’s another side to the story—one where Nheras and Rahelu’s roles are reversed.

- Hint at Nheras’s motives and her relative standing amongst the other House-born.

I tried very hard to stay away from doing this via clumsy exposition. Not only because I hate it, but because we’re in Rahelu’s POV. She views all House-born as a monolithic entity and has neither the inclination nor the opportunity to learn anything more. Anything I wanted to convey, I needed to convey via implication and subtext.

Did it work? It’s a little heavier-handed than I would like, but I think so. At the very least, the published version is far better than the draft.

Tone and story promises

I had two big problems with my draft.

First (and most significant) was the two halves of my book read like totally different stories. It begins with essentially a tournament arc—Rahelu and her Petition—then halfway through, it takes a left turn into a murder mystery. (More on this in the annotation on the prologue and the annotation on Chapter 3.)

Second problem was the incompleteness of tone promises and consistency of tone throughout the opening chapters. I did not want somebody picking up this book, thinking it was YA fantasy, and then subsequently being horrified by the swearing, violence, and sexual content.

Expanding the exchange between the Ilyn applicants and Rahelu served a few purposes.

1. Spreading the dialogue between Nheras, Bhemol, and Kiran conveyed a better sense of their dynamic and established some distinctions in their respective characters.

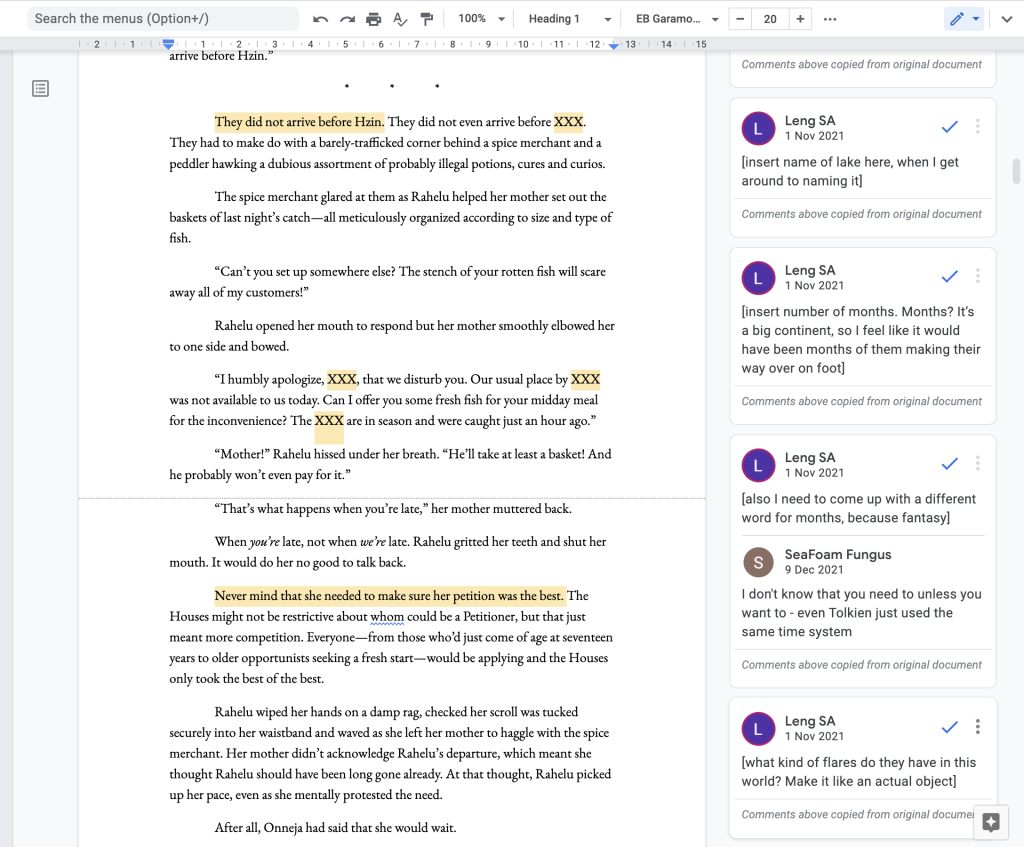

2. In the beta read draft, Kiran already had an expanded role, though the scene was less sexually explicit:

I think Kiran’s implication here is clear but some of my beta readers were still caught off guard by the last scene in Chapter 11, which sets up two other scenes in Chapter 22. (The end of Chapter 11 is roughly 46,000 words into the book, which is far too late to be setting up tone and story promises. Those all need to be in place by the end of Chapter 2, which is about where the sample chapters on Amazon end.)

The other issue is, while we get Rahelu’s reaction, we don’t understand how she feels about the situation or the power dynamics in the world. The two additional paragraphs in the published version help bridge that gap.

3. Finally, there was an opportunity here to draw a clearer parallel between Tsenjhe and Rahelu, which is important for setting up some of Rahelu’s later choices.

Ending

In addition to splitting off the whole sequence from Market Square to Rahelu’s Petition being destroyed into its own chapter, I also changed the ending based on alpha reader feedback.

Originally, this sequence ended with Rahelu being devastated by the destruction of her Petition and Nheras stalking off. It’s a real downer of an ending and the version that I, and a few of my beta readers, personally prefer.

But when I stepped back to take a look at the overall structure of the book, I noticed my tendency to end chapters on emotional gut punches—perhaps because I conceive of them as self-contained arcs. Many of my early drafts lacked an explicit hook into the next chapter which was a recurring piece of feedback from my alpha readers. (The most common reaction was ‘what now?’ but not in a way that compelled them to go on to the next chapter.) This kind of chapter ending (mostly) works for the second half of the book as, by then, you’ve become invested in the characters.

But when we’re only at Chapter 2 and still in the sample chapters, it’s a big risk to take. I don’t have the marketing budget or the marketing department of a traditional publishing house behind me. Every reader I can convince to visit the product page for my book and click through to the sample is precious to me. If you’ve gotten to the end of Chapter 2, which has set up all of the story and tone promises, chances are you enjoyed my writing enough to read through to the end.

It might not be the creative choice I prefer, but adding the more obvious hook in here was probably the safer, more commercial decision.

Maybe someday, when I’ve built enough trust with readers, I can take some more risks creatively. But for now, I’m focusing on doing whatever I can to prevent the dreaded ‘DNF’.