One of the decisions I’d made from the very beginning was that Petition was going to be single POV. I didn’t want to fall into the typical epic fantasy author trap of POV bloat that would land me in revision hell; I wanted to write a clean draft of a tightly-focused narrative.

(By the way, I’m sitting here writing this annotation after completing a first read through of the rough draft for Supplicant—which has…issues. Turns out that the choice of a single POV doesn’t necessarily help; it was the strict tournament plot structure and Rahelu’s singular goal that kept everything focused.)

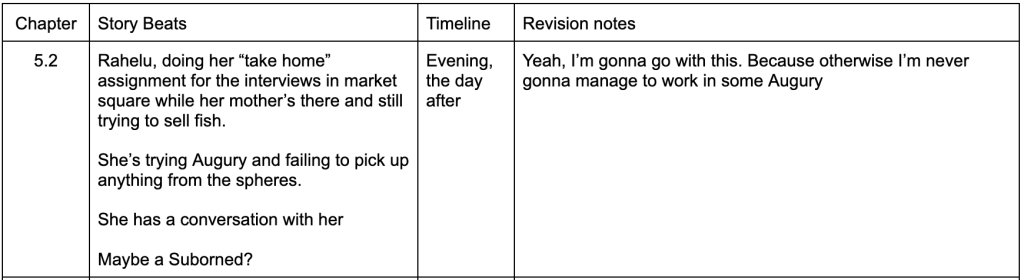

As usual, I did not have a very detailed outline going into this chapter:

But what I had was a secret pet peeve.

Interviews are dumb

The main plot is fantasy job interviews and we’ve already done the job application and the group interview. The next stage in real life is usually individual interviews but let’s be real: an interview is a poor method of trying to figure out whether someone is going to be a good hire or not.

How is a super awkward 15-minute conversation in a sterile meeting room where you’re cherrypicking from a list of HR pre-approved questions (and trust me, you do not want to be going off-script as an interviewer; not only does that introduce even more bias into the process, it also makes everything that comes afterwards even harder) and the interviewee is doing their best imitation of a politician on campaign to spin their pre-rehearsed lines into a satisfactory answer going to tell you anything about how they will actually do on the job?

It relies on a whole bunch of shorthand approximations to infer ability and competence from a performance that has no relevance to what the actual job is.

Unless the job involves being interviewed, I guess.

Anyway, the process is stupid. The best way to figure out if someone can do something is…to get them to do the thing.

Hence the take home assignment.

(Confession: I had no idea what the spheres do when I wrote this scene. The nice thing about writing from Rahelu’s POV is that she has no idea either…and it doesn’t matter. For this book anyway.)

Yes, yes, it means you don’t control the environment in which those assignments are completed and therefore you can’t be assured that it’s the candidate doing the actual work instead of somebody else.

To which the Houses would say: who cares? The work got done. Also, the magic system literally allows us to check whether you’re lying about it being your work and/or check how you went about completing the assignment.

How Seeking works

My beta readers did wonder why it took so long to get an explanation with Seeking which ties in with this comment:

The other thing that annoyed me a bit concerned the world-building – the author introduced various terms describing powers/resonances by naming them without explaining their effect. But then, again, it’s easy to get the hang of it quickly, so maybe I’m just nitpicking a bit.

—Goodreads review

There were a few reasons behind this decision:

- Reading Steven Erikson’s Malazan Book of the Fallen series made me hypersensitive to exposition. It’s like entering the Matrix: once you’re aware of it, you can’t unsee it. Exposition is everywhere.

- I did not want to get the criticism that Brandon Sanderson gets for his Szeth prologue in The Way of Kings (i.e. it reads like a video game tutorial for Windrunner powers).

- There’s no reason for Rahelu to stop and think about how Seeking (or how any of the other resonance disciplines) work as she’s going about her daily business.

One trope I dislike in the fantasy genre is the whole “born with special powers” thing. That’s why I made magic is an intrinsic part of the world. Everybody in this world has resonance ability as a sixth sense and you can learn to do more with it if you choose to. Some people might be more naturally talented—just like how some people are born more athletic or artistic or whatever—but that’s all.

Rahelu stopping to explain how Projection works as she’s running up the hill to stop the Isonn baliff from roughing up her mother or how Seeking works as she’s trying to run away from Nheras and her cousins isn’t authentic to the character—it’d stick out as much as a character stopping to think about how they make their body walk. In these two instances, Rahelu is a graduated mage using her powers in magically straightforward situations: her concern isn’t how her powers work but whether she can protect her mother and whether she can escape with her Petition. Explaining the magic here would bog down the pacing and detract from the emotional intensity of the scene.

But when Rahelu struggles to complete her take home assignment, it does make sense for her to think about how resonance works. She’s attempting Augury, a discipline that she has no natural aptitude for, trying to follow Dharyas’s advice. It’s natural for her to think about how she does what she does as she’s doing it.

In short, I made a stylistic choice to not explain the magic system because it isn’t necessary. Between the names of the various resonance disciplines and the descriptive details on what happens when the characters use them, there’s enough on the page for a reader to infer how the magic works.

Hzin

My beta readers also had questions about this character and the overtness of the Augury. In particular, they felt it was tonally jarring and a departure from the rest of the story.

I tried to fix the tonal inconsistencies by expanding the confrontation between Rahelu and Kiran back in Chapter 2. But that still begs the question: why?

Why include sexual violence? Why include sexual exploitation? Why have sexual content at all? (Which we’ll talk more about in the annotations for Chapter 22.)

It’s a controversial decision. Many readers actively avoid books with sexual violence. Many more have taken the stance that there is already enough sexual violence both in fiction and in real life that we don’t need more of it. Especially when sexual violence in the fantasy genre (and let’s face it, in general) is often used gratuitously and is not sensitively depicted.

Readers (and authors) on the other side of the argument have offered many rebuttals. I won’t go into those here because they’re not really relevant to my decision.

In my experience, sexual violence isn’t really about the sexual aspect of the violence; it is about control. And in this setting—when the magic inherent in this world literally allows one person to override another person’s emotions, as Nheras demonstrates in Chapter 8—the uncomfortable question can’t be avoided, especially in a new adult/adult novel.

(Let’s temporarily shelve discussion of the other question of how Petition is sometimes categorized as YA for another time.)

To draw an arbitrary line felt disingenuous in a story that explores what people are willing to do for the sake of power.

Power, fundamentally, is about control.

There are some things about our world that I can easily imagine to be absent in a secondary world. Gender roles, for example, is one. I’ve spent my whole life proving that my gender doesn’t make me any less capable just because I’m not male. And I’ve been very fortunate to be born at a time and in a set of circumstances where I’ve never had reason to doubt this to be true.

The threat of sexual violence, however, is something that I—and every other person born female—live with. From the moment you’re old enough to be told “you’re a girl”, you’re also taught very specific things that aren’t taught to boys.

How to sit.

How to dress.

How to act.

All of these things are taught to young girls as preventative measures in an effort to protect them from the possibility of sexual violence. And you internalize these things so much that you can’t see the world except through those lens. And you modify your behavior accordingly.

Perhaps another author could imagine a world where sexual violence doesn’t even enter into the equation because it isn’t a possibility in their setting.

I, unfortunately, can’t.

Leave a Reply