I’m not much of an audiobook listener. The only time audiobooks work for me is when I’m doing something that occupies my hands and immediate attention, but the work is not cognitively demanding enough to occupy most of my brain. Like cleaning. Or highway driving. Otherwise, my mind tends to wander off after a few sentences and I inevitably end up constantly rewinding.

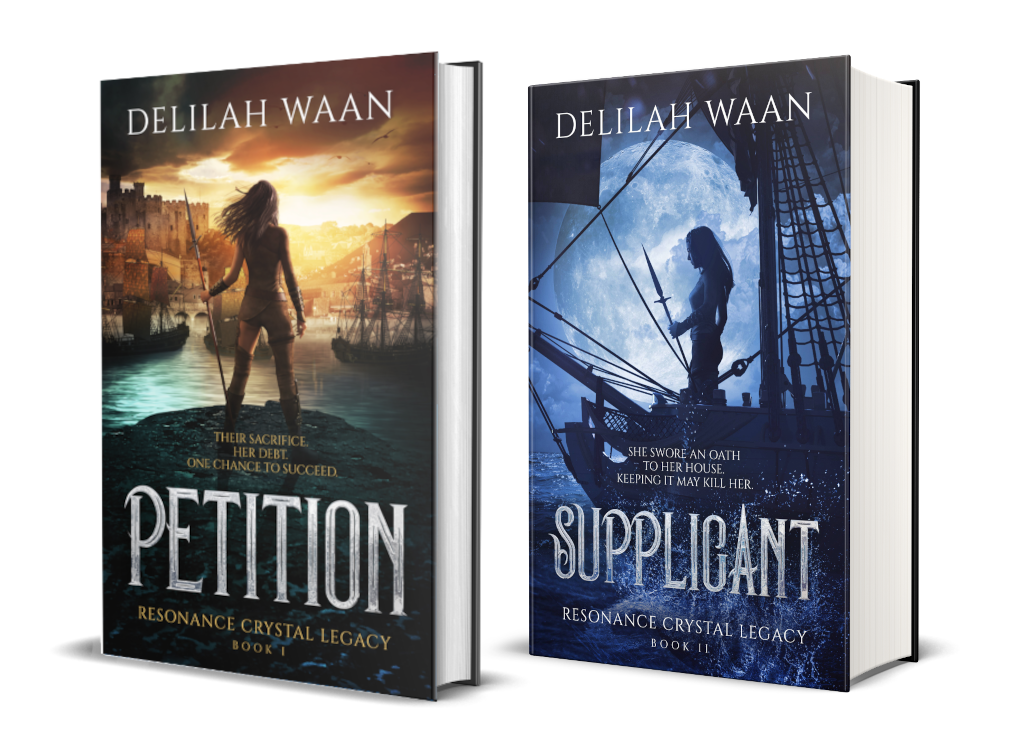

In addition, audiobook production is expensive. The standard minimum SAG-AFTRA union rate to hire a professional narrator is $250 USD per finished hour of audio. More experienced narrators charge significantly more. Pace varies according to the individual narrator and manuscript, but as a general guide, 8,000–10,000 words translates to roughly 1 finished hour of audio. At approximately 115,000 words long, an audiobook of Petition would come in at anywhere between 11.5 and 14 hrs (the final run time is 13 hrs and 43 mins) or $2,875–$3,500 USD. Using today’s exchange rate of 1 AUD = 0.66 USD, that meant the starting price tag to produce an audiobook of Petition came in somewhere around $4,400–$5,300 AUD mark!

…yeah.

If it had not been for: a) the generous 2023 cash grant I received from the Indie Fantasy Fund; and b) a “Hail Mary” source of personal funding that came through last minute, I wouldn’t’ve been able to hire Emily Woo Zeller to narrate Petition.

Needless to say, when I was writing and revising this book, I didn’t really consider how the story would come across when narrated; I was focused on strengthening emotional arcs, eliminating repetitive beats and word choices, and concentrating on the rhythm, prosody, and flow of the prose. Improving those things typically also improves the experience for audiobook listeners—if a sentence reads well on the page, it generally also reads well spoken aloud—except for scenes where the medium of delivery significantly affects how much information can be conveyed in a single line.

Like scenes with high stakes, emotionally charged dialogue.

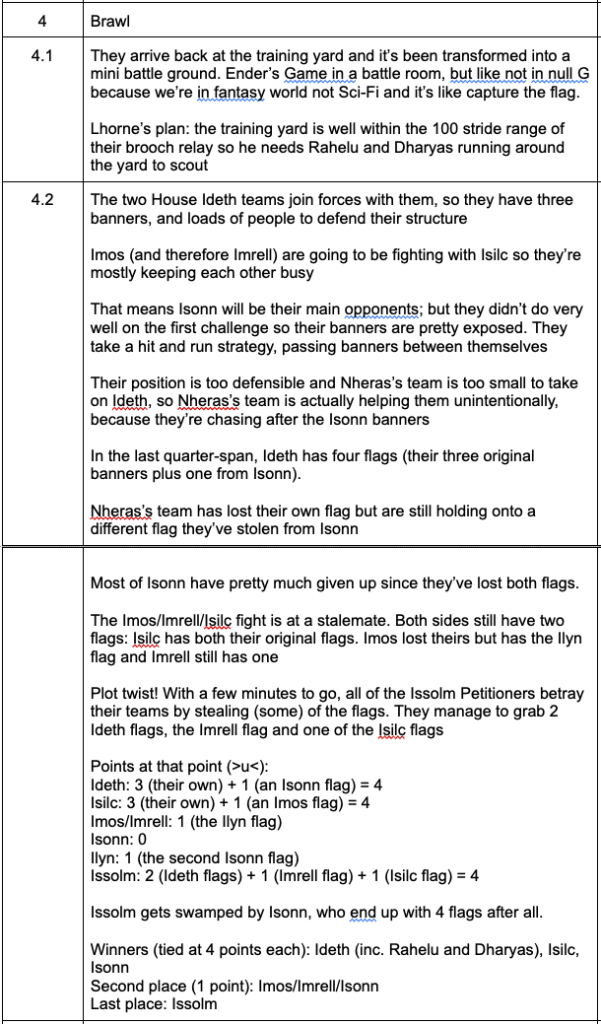

The core of this chapter is the clash between Rahelu and Lhorne regarding her choice of House, a conflict centered in their differing experiences and worldviews. It’s about 1,660 words long, beginning on page 349 in the retail hardcover and coming to a crux on page 353.

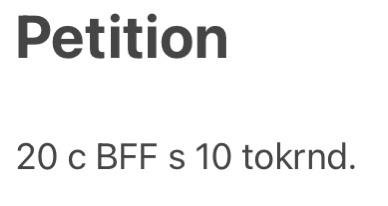

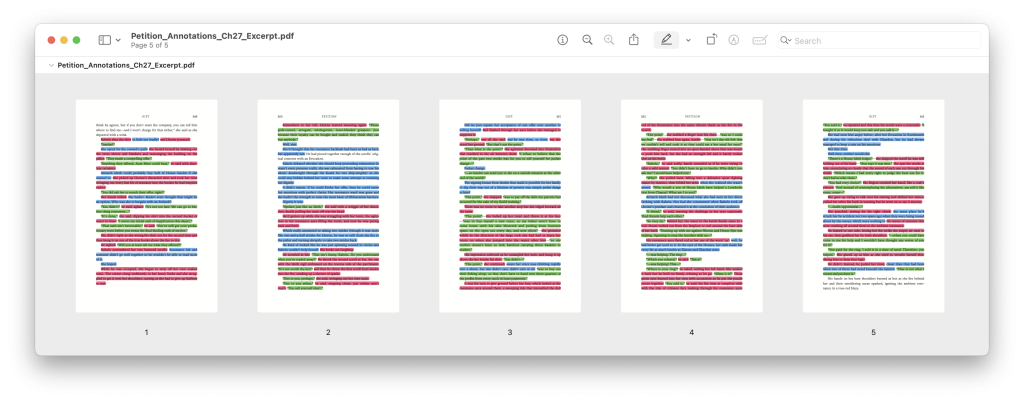

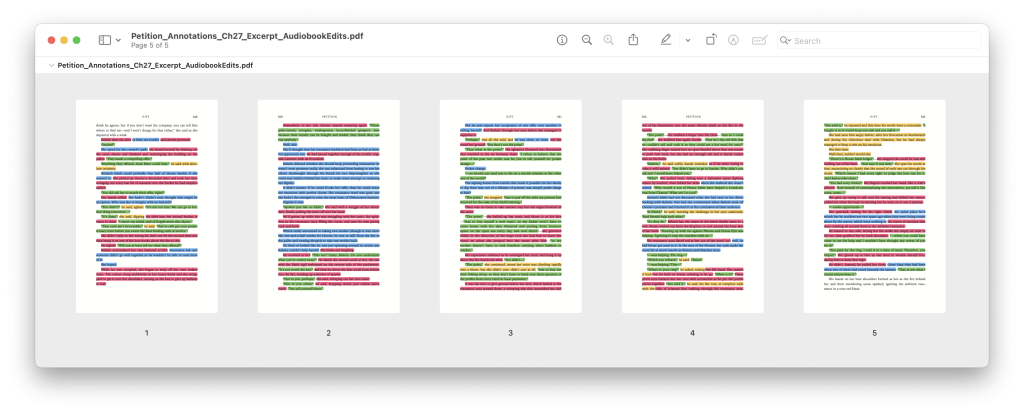

An interesting exercise I like to do when considering whether the balance of a scene is off: I go through the text and highlight with specific, assigned colors to differentiate the various components:

- Dialogue (green): defined as all direct forms of communication between characters, which includes things like telepathy and written letters.

- Action (red): defined as characters acting upon (or being acted upon by) their environment/others, including phenomena like magic and whatever else is directly observable by the viewpoint.

- Introspection (blue): defined as any personal interjections, opinions and/or interpretations of dialogue or action from the viewpoint character.

Here’s what this scene looks like after doing the highlighting exercise:

Note the high proportion of red (action, ~745 words/45%) and blue (introspection, ~425 words/25%) there is relative to the green (dialogue, ~500 words/30%). In the audiobook, the scene runs from 13:05:50 to 13:17:17. Using the proportions from the highlighting exercise as an approximation, it means we’ve effectively got a 4-minute exchange stretched out over nearly 13 minutes. Mostly, that’s due to how prose functions as a medium; dialogue needs to be supplemented with action and introspection in order to convey the fullness of what’s going on in the scene. In film or theatre, however, this would be done through the set design and by the performance of the actor/s.

So what does that mean for audiobooks?

Well, some action and introspection is still necessary, because we don’t have a set and we can’t see the narrator’s facial expressions, body language, and physical actions. We do, however, get character voice, tone, inflection, and more, through the choices the narrator makes in how to deliver a particular line of dialogue (Note 1) which means there are bits of text that no longer serve a purpose, as the non-verbal aspects of the dialogue are all conveyed through the narrator’s performance.

Me, replying to Emily and her audio engineer right after I finished listening to the mastered audio files: Chapter 27, my god. I wish I had written less introspection so my words can stop interrupting Emily’s amazing delivery of the characters’ dialogue.

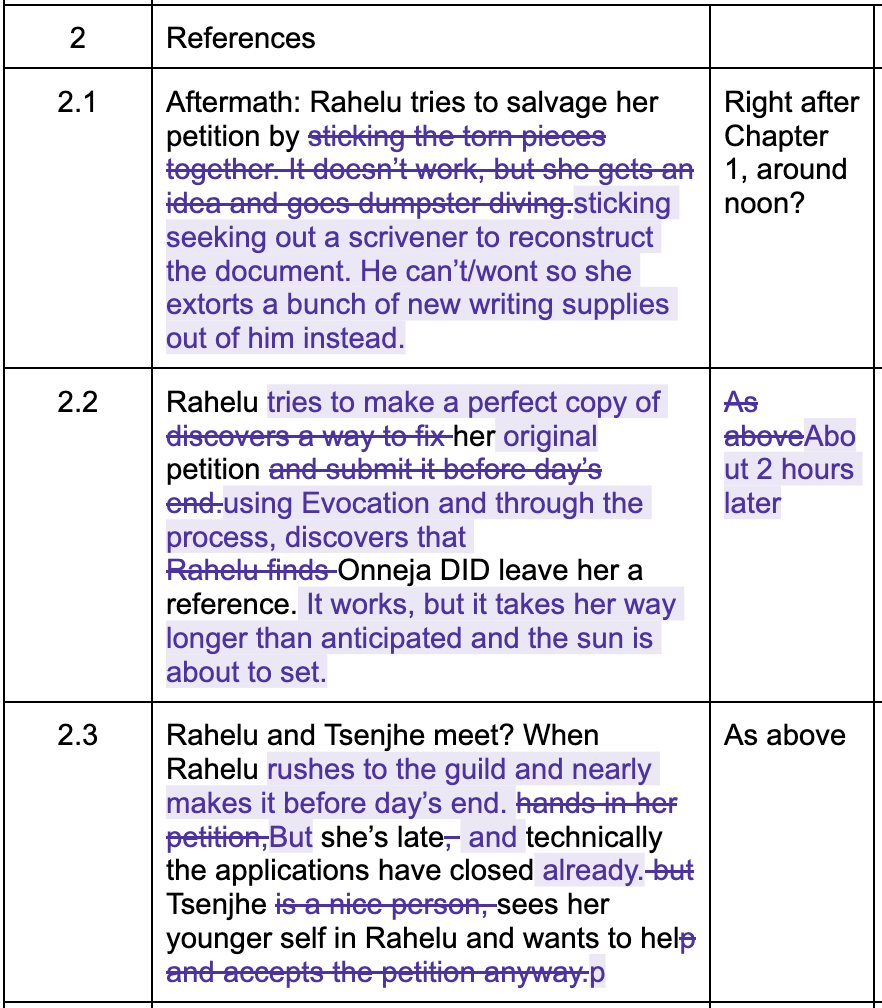

Here’s a visual with what I wish I would’ve done differently. Yellow highlights are lines that I’d rework or outright delete for narration:

Not a lot I would change—only about ~145 words (less than 9%) or so—but note the increasing amount of words highlighted in yellow as the tension climbs in the third (25/315), fourth (31/370), and final page (67/330) of the scene. I personally think it would have a huge impact on the perceived pacing and flow of the scene when you’re listening, and it’s something I’m definitely keeping in mind for future books.

As to what Rahelu does on the next page right after this scene…

My writing group was not pleased with me:

GODDAMNIT

YOU MADE ME FEEL FEELINGS

I SHIPPED

SO HARD

I HAVE Only one question

Kiss him, dammit!!! KISS HIM!

She should have KISSED LHORNE DAMMIT!!!!!

And if you felt particularly blue-balled, then maybe it’ll make you feel better to know that, ever since, half the time I post in our Discord about struggling with a scene, they now just spam writing advice like this:

Where they kiss, right????

Have them kiss and make up instead

now kiss

they kiss

If anything toss the scenes where they don’t kiss

These heroes better be smooching

Or I may have to write a strongly worded letter to the resonance guild

And memes like this:

More seriously, though, they really go all out to keep me sane. While I was struggling with alpha revisions and showing clear signs of spiralling, Dan Harris kindly took the time to give me some stellar constructive criticism:

Click here to read Dan’s suggestions

I hope you don’t mind but I’ve been thinking of the structural issues in your book and how to fix them. So I’ve written this. It’s an extra scene with Nheras (something you were thinking about) and also hopefully ties the murder plot into something more personal. Obviously it’s your book so please take it or leave it but I hope it’s helpful.

Petition – suggested improvements

By Daniel Harrison

(Spoilers for the unimproved Petition)

Rahelu emerged from her sleeping berth and into the bath house. The air was thick with steam, so thick she could barely see where she was going.

But she knew that she wasn’t alone in there. She could sense the pulsing, blue aura of masculinity coming from the bath. She was hoping to make it through unnoticed, but when she was almost at the door, Lhorne’s voice called out to her.

“Rahelu? Where are you going?”

She swore silently to herself and tightened her grip on her spear.

“You know where I’m going. There’s a murderer out there. Someone needs to catch them. We can’t all wallow in the bath all night.”

“Wait and I’ll come with you. You shouldn’t go out there alone.”

Silly, House-born Lhorne. He didn’t understand. She’d always been alone. Just her and her parents. And they probably wouldn’t be very good at fighting cultists.

She didn’t reply, but like an eel she slipped through the door and out into the night.

It was dark outside. Not just because it was night. But also because the stars were hidden by clouds. Also it was raining. Not heavy rain, but enough to coat the cobblestones in a thin sheen of water that made them reflect the torchlight in a really atmospheric way. If they even had torches in this universe? Yes, Rahelu decided. Yes, they did.

For about half a span, Rahelu had been wandering the streets like a hunting shark fish and she was beginning to think that it was a fruitless exercise. But then she saw something. Not with her normal vision, but with her magical aura vision. From one of the alleyways she saw the faint but unmistakable green shimmer of bitchiness.

She crept forward silently like a fish in the night, and peered into the gloom of the alleyway. But she already knew who she would find there.

“Nheras,” she growled.

The young woman was wearing a slinky and revealing dress, despite the rain. It probably cost more than all the dresses Rahelu had ever owned.

“What are you doing here, Nheras?” Rahelu asked, stepping into the alley.

Nheras looked around and sneered. “I don’t need to justify myself to you. What are you doing here, fishface?”

Rahelu screwed up her face like a trout. She didn’t like being compared to a fish. “You know what? I’ve had enough of you.”

Rahelu let her spear clatter to the floor and she launched herself forward, seizing the other woman who gave a brief cry of surprise.

Anger coursing through her veins, Rahelu tore the slinky and revealing dress from Nheras. A gasp escaped her lips.

Underneath the slinky and revealing dress, Nheras was wearing thick, black robes.

“You?” Rahelu gasped. “You’re one of the mysterious cultists?”

Nheras laughed. “Now you know too much. I’ve been waiting for an excuse to do this. I’m going to gut you like a fish!” She drew a wicked, curved blade from the folds of her robe and raised it up, ready to strike.

“Not so fast!” a voice boomed from the mouth of the alleyway.

Rahelu looked up. “Lhorne!”

Lhorne met her eyes. “You’re never alone, Rahelu. Not while I’m with you.”

With that he pulled back one of his big, masculine arms, and punched Nheras right in the face. She went limp as a boned fish and fell to the filthy alley floor with a squelch.

“Oh, Lhorne!” Rahelu smiled. But Lorne wasn’t smiling back. “What’s the matter?”

“It’s this damn rain,” Lhorne said. “It’s made my shirt all damp. Not really damp, but that uncomfortable kind of damp. I’m going to have to take it off.” And so saying, he pulled his expensive linen shirt off and tossed it uncaringly onto the ground. Rahelu looked at his masculine chest.

Lhorne put a finger under Rahelu’s chin and guided her eyes up to his. “Kiss me. Kiss me right now,” he said.

“What’s the rush? We have all the time in the world.”

“I don’t know,” Lhorne said, looking away. “Sometimes I feel like the sexual tension between us just ramps up and up but we never get the sweet release of a kiss.”

“Not this time,” Rahelu replied. “We can take our time and make this the most perfect kiss.”

But then she looked at the ground and cried out. “Nheras! She’s gone! She must have slithered away while I was looking at your chest.”

With that, she snatched up her spear and dashed from the alleyway in hot pursuit.

Lhorne watched her disappear into the night. “Oh, darn,” he sighed. “I appear to have switched POV.”

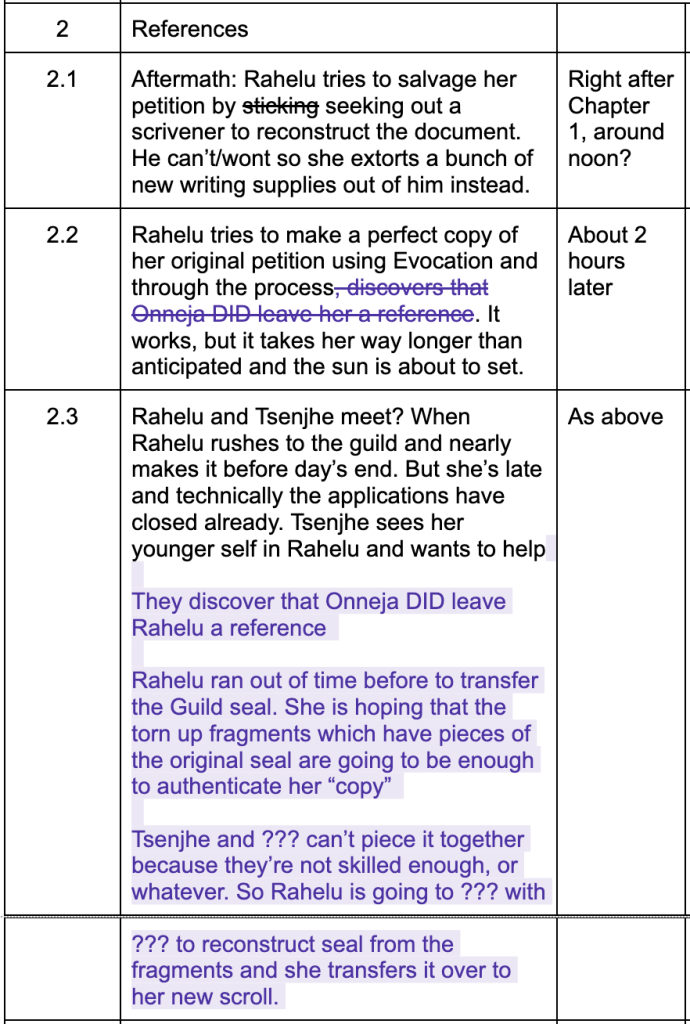

Click here for my reaction

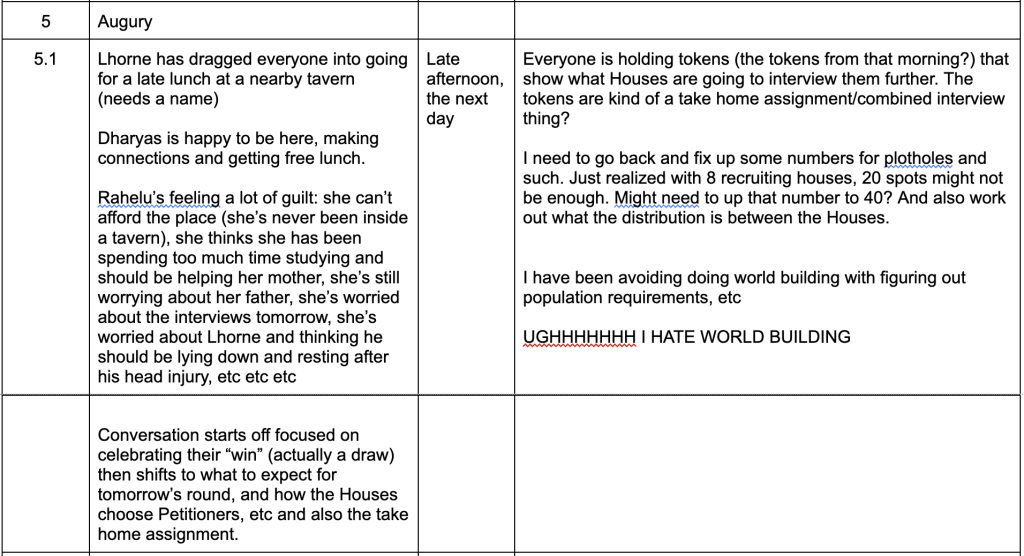

![A screenshot from Discord with the following text:

🤣 holy shit this is awesome

😆

I'm dying

This is the greatest thing ever

[Dan's @Discord] you absolute champ I'm in stitches

[Reactions: 4 😆 1 😂]

OMFG

My family's asleep you know, it's killing me not to laugh out loud](https://www.delilahwaan.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Delilah_Reaction_Dan_Harris_Suggestions-1024x567.png)

Dan is way funnier than I am without even trying.

Truly, my writing group is the best.

By the way, if you enjoyed that and you’d like to check out more of Dan’s work, he’s got an urban fantasy novella series that’s a bit like Men in Black meets Ghostbusters: office comedy edition as well as a series of very British cozy murder mysteries.

Note 1: Totally not the place for me to go into a full rant about why the “but what about accessibility for vision-impaired readers, etc” argument in favor of AI narration doesn’t hold up, but I do feel it’s important to point out the distinction between making something accessible and wanting (dare I say, to the point of entitlement) performance. If you’re interested in my thoughts, I had a longer discussion on the subject with some fellow authors over on JCM Berne’s channel. (return to text)